Reflections on Why has Indonesia never won a Nobel Prize?

Published:

There is this pdf that is forwarded many times on Indonesian academia whatsapp groups: “Why has Indonesia never won a Nobel Prize”. The pdf talks about the lack of research culture in Indonesia and the failure of Indonesian universities. It attempts to analyze why it is only Indonesia (of all countries in South East Asia) that has never won a nobel prize.

When I came across this, I found myself contemplating a similar question. I attempted to discuss this matters with my Indonesian friends about the apparent scarcity of Indonesians compared to kids from neighboring countries such as Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, who appear to have a more significant presence abroad. There is a sentiment among us that people from these neighboring nations are more internationalized than Indonesians.

The challenges of international exposure for Indonesians

Last year, I was granted funding through postgraduate scholarship program from the Directorate General of High Education Research and Technology (DGHERT) Indonesia. The purpose was to undertake one-semester PhD research abroad. This opportunity was also given to other 35 qualified Indonesian PhD candidates, all recipients of the same postgraduate scholarship program. To provide a brief overview (considering the challenges I faced with DGHERT officials and other aspects), my research visit took place in South Korea. Fellow awardees explored destinations ranging from Europe to America, with 40% choosing Japan.

During my research visit to South Korea, I made friends with some international students there. I knew that there were also several other postgraduate Indonesian students in South Korea, though not as many as the other nationalities, especially the neighboring countries. However, the Indonesians were not so helpful to me, while my other international friends, who at first were also stranger were very supportive. I was not asking much from them (Indonesians), only some little key-point information, yet they seemed to be reluctant to share. It was instead my international friends who were very open about various information.

I might be too negative thinking about people from my own country, but I had a strange feeling that these Indonesians might not want me to come to South Korea. Somehow, this may not be simply just my opinion, but rather a refelction of the Indonesian mentality, as stated by the Peter Carey in the pdf: Indonesia did have some potential figures to be receiving the Nobel Prize, but were hindered by the government, and or the people.

Investigating the Research Culture

Motivated by Peter Carey’s observations on Indonesia’s research culture (full article here, I delved into the issues surrounding higher education and research sectors in Indonesia. As both an Indonesian and a scientist, I resonate with his criticisms and have much to share on the subject.

Indonesia Postgraduate Scholarship: An Overlooked Gem

I recently began the process of obtaining my Master’s and PhD through the DGHERT Indonesia scholarship program, called PMDSU, an opportunity that I believe has the potential to make a significant impact on the academic landscape in Indonesia. However, I have noticed that this scholarship program is not as well-known in our country as it deserves to be. In this post, I want to share my thoughts on how we can collectively raise awareness about this incredible opportunity.

This program holds great potential, providing a valuable opportunity for fresh graduates from diverse backgrounds across Indonesia, including those, like myself, from a small town, to pursue postgraduate studies. Unfortunately, the program’s promotion on social media and its official website are completely ineffectual in highlighting its benefits and potentials.

Furthermore, I would want to bring attention to a crucial observation about accessibility. The official website is presently only available in Indonesian. Recognizing the program’s potential for international effect, I respectfully suggest including an English version to broaden its reach. Ensuring the availability of information in both languages is consistent with the program’s goal of worldwide recognition. For your convenience, I have created an English version of the website using Google Site Translator.

Website home page: https://www.pmdsu.id/

Website about page: https://www.pmdsu.id/tentang/

Website mechanism page https://www.pmdsu.id/mekanisme/

This is what in the home page:

We do not get to see much information in the homepage. I assume that there should be a simple overview of the scholarship, but instead it just gives us some quotes by the Director. For someone who never knew about this scholarship, I think it will just confuse them more.

There are some news and announcement link in the homepage, but I still feel that is too much. Also there is “About PMDSU” that gives us overview of the scholarship, but I honestly feel that they use a very confusing word choices.

What is wrong with the Indonesian scholarship website?

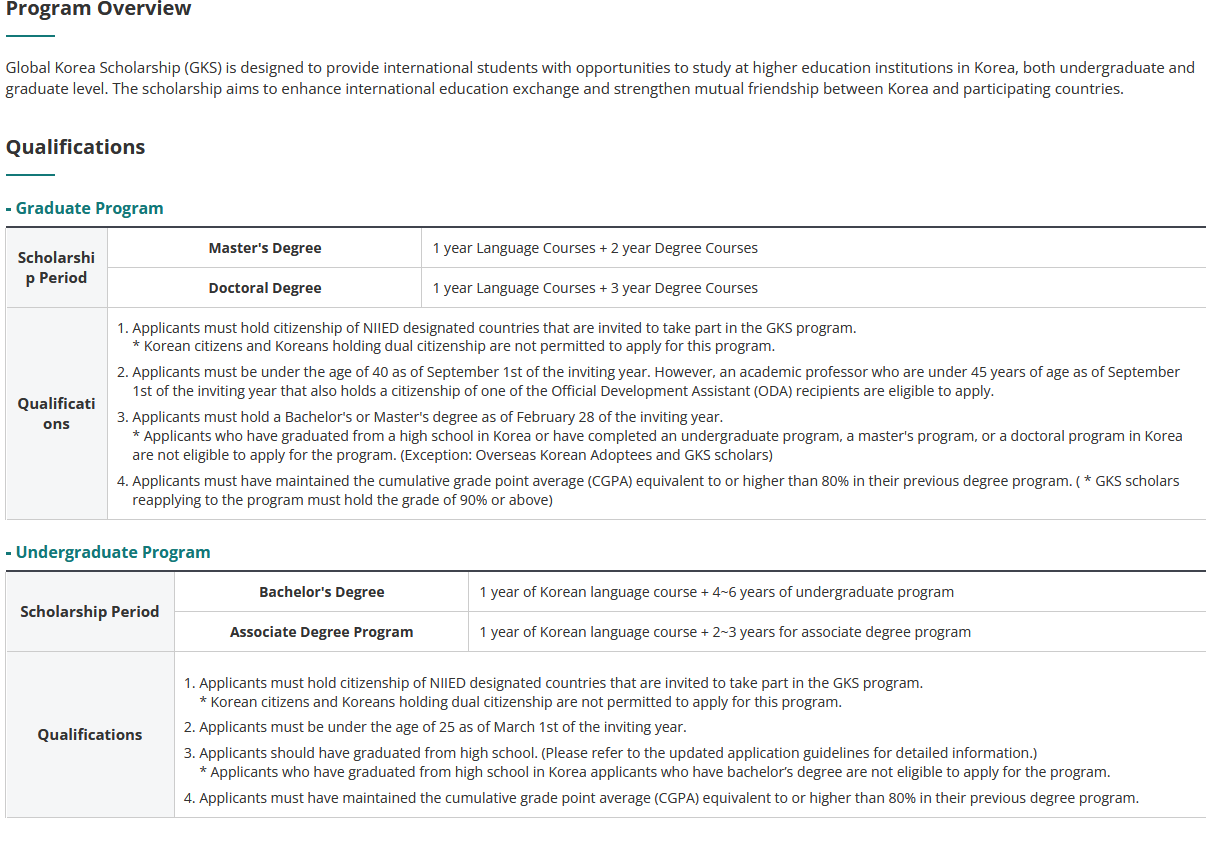

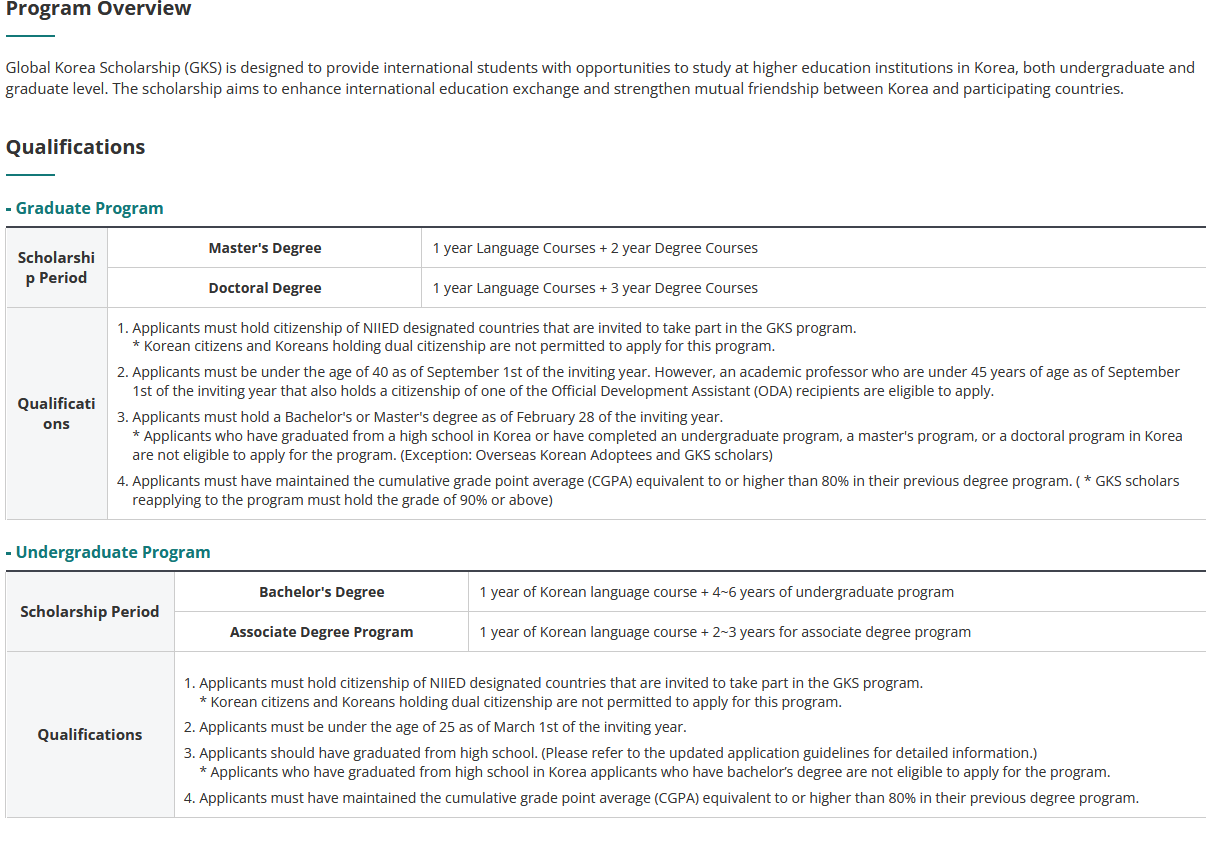

Let’s compare it with other international scholarship. I can think about Global Korea Scholarship (GKS) for now, since it is very popular for Indonesian students.

This is the GKS webpage: http://www.niied.go.kr

There are clear differences between the Indonesian and Korean scholarship websites. The Korean scholarship website is very informative about its scholarship information, beginning with a program overview, qualifications, selection procedure, and scholarship benefits. On the other hand, Indonesian scholarship website contains ambiguous information; we have to be very alert to locate some crucial information by scrolling, clicking on numerous buttons to visit various pages.

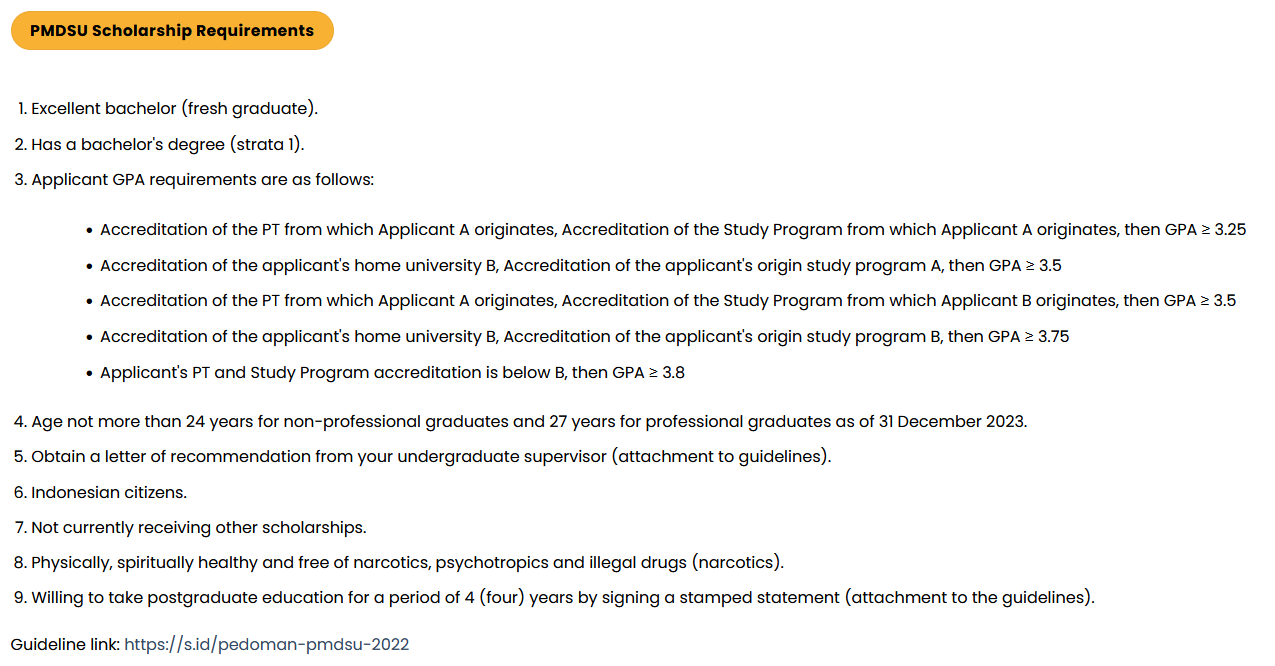

For example, when you want to find out about the qualifications/requirements for you to apply for the scholarship, you have to scroll down below in the mechanism page. Because at this page, you will find several requirements: starting from the scholarship requirements targeted for the host university and professors who want to have in-take PhD students using this program. Meanwhile, and for the students who want to apply for this scholarship, they must be very confused (I have experienced it before). And finally, when we scroll down, we will find the requirements for the students. However, the title itself “PMDSU scholarship requirements” is not so clear, like is this the right information targeted for the students? I can only tell that it is, because I have applied for it before.

The detailed mechanism and procedures for the scholarship are even more absurd. They even made a whole book (22 pages) in Indonesian regarding the scholarship requirements and procedures for the candidates: here, while you can really summarize it for at least 3-pages pdf (5 pages at max with the attachments for the letters to sign by the applicants). At first, I thought it was normal, but as I got more international exposure, I realized that some international scholarship from other countries can be very easy to understand and they put their procedures just in a 2-page pdf or in a one page website.

When I first wanted to apply for the scholarship, I really felt so dumb, because it seemed like I was not so observant and literate enough to find the key-point information, until I realized that it was not my mistake. It is just that the website is simply designed like to make us feel dumb, to make us feel that it is our mistake when we miss some information. This kind of gatekeeping action is not only some Indonesian scholarships website, but we can also find them on civil servant application website, etc.

So why is the Indonesian government websites designed like this?

The research conducted by Peter Carey in Why has Indonesia never won a Nobel Prize? may have covered this problem clearly, especially related to the recruitments of Indonsian lecturers. Many of Indonesians would love to stay in their home institution to be a civil servant (a lecturer). I quote:

“This condition has led to academic inbreeding, whereby academics are employed through closed and semi-closed recruitment methods, and a great many of them choose to stay within the safety of their own home institutions when pursuing higher degrees.”

So, the answer to the question “Why are the indonesian government websites designed this way?” is simply because the Indonesian officials want to make it easier for specific people to become civil servant rapidly. As Peter Carey pointed out, this measure is specifically intended to help special individuals, and those special people may include officials’ children. We can’t deny how beneficial it would be for many Indonesians to become civil servants. It’s a dream job.

Big result with small effort (Civil servant is a dream job)

I know that this is not only in Indonesia, and even in South Korea, people have a dream to become a civil servant, since this job offers stability. However, the motivation and practice might be different between Indonesians and Koreans. When Koreans really want stability to be a civil servant, it is purely because they want the stability and would not mind the hard work later too. Also, most of them who want it might come from middle to lower class. However, for Indonesians, they want to be civil servant just because this job offers the easiest workloads. This is the reason why even those from higher position are so eager to get this job.

So, I am not making this up when I tell you that I have some extended relatives who dare to pay for hundreds of millions Indonesian rupiah (IDR) or even up to 1 billion IDR just to become a civil servant, such as school teacher, policeman, army, prosecutor, and even just prosecutor’s assistant, etc. And the entrance price for you to pay depends on the position that you will get. This is kinda absurd, becasue the lifetime salary in total for that job might not reach more the bribe money. However, there is this strong believe in Indonesia that money that you get from corruption is also your salary. Do not judge me for making it up. I know that this is very crazy.

This absurdism regarding Indonesian civil servant has been put into spotlight by Peter Carey’s work, Why has Indonesia never won a Nobel Prize?, which I quote:

We recall here the recent words of the Indonesian historian, Anhar Gonggong, “We once had leaders of the calibre of Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta, Sjahrir, Tan Malaka, who were each able to carry out their own mental revolutions, but now we no longer have national leaders [statesmen]. Instead, we just have civil servants (pejabat).

Other than Peter Carey’s observation, more of this absurdism has also even been covered in details by Elisabeth Pisani in her book, Indonesia, Etc..

The failure of Indonesian Postgraduate Scholarship to advance Indonesian research (low quality publications)

Related to the prevalent motivation of securing a civil servant position as a dream job for many Indonesians, I’ve come to grasp why some might label me an idealist due to my alignment with Western perspectives. It may be surprising for Indonesian audiences to hear that my pursuit of a Ph.D. is driven by a passion for research. Initially, upon entering the postgraduate program, particularly through this scholarship, I hoped to encounter other individuals who shared similar aspirations like me. However, I found that my peers from the undergraduate program in my department at the university demonstrated superior skills, knowledge, and perspectives compared to current PhD peers.

Understanding this reality, it seems reasonable to say that the scholarship falls short of its intended impact. It may appear contradictory for me to make this statement, given that I am a recipient of the scholarship; labeling it as a failure might imply my own failure. What I intended to convey, however, the initiative and ambition of the scholarship program are not a failure. To be honest, it is great to know this country has established such a program. As highlighted by Peter Carey, money has never been the main issue. However, the practice and motivation by most of the awardess and professors are just simply ineffective.

In my case, I can confidently state that I have put forth my best effort. While acknowledging that my achievements may not possess the glamour of PhD candidates from more economically developed countries, I can affirm that they align with international standards. It is not my intention to boast, but rather to emphasize that my accomplishments surpass those of many other PhD fellows within the same scholarship program.

For a fair comparison, I present the official website of the scholarship program, which compiles a list and statistics of publications by recipients of the PMDSU scholarship. You can access the publication list and statistic of publication by PMDSU awardees spanning from the first batch to the current seventh batch (with my affiliation being from batch 5).

From the provided list, a considerable number of the papers lack publication in reputable venues and can be categorized as submissions to predatory journals. Only a handful have been published in esteemed publishers such as Elsevier, Springer, etc. (acknowledging the ongoing debates surrounding these publishers). It’s worth noting that the scholarship program does not recognize contributions in the form of conference or workshop papers, even if they are published in well-regarded venues like CVPR, MICCAI, etc. The emphasis appears to be solely on journal publications, without consideration for alternative forms of scholarly dissemination.

The situation is rather unconventional. Some recipients from various batches have received extensive acclaim for their prolific publication records, with some producing as many as 140 papers within the four-year span of their master’s and Ph.D. programs. This may seem surprising. Initially, I found their achievements impressive, particularly in my first year. However, with increased exposure to international standards, I have come to realize that many of their publications appear in predatory journals. Despite this, they receive substantial recognition from scholarship officials, frequently being invited to participate in talks and seminars organized by DGHERT. My intention is not to criticize out of envy for their recognition; rather, it raises concerns about the evaluation criteria. This situation appears to reflect a disparity in acknowledging genuine scientific contributions.

Another notable aspect concerns the one-semester research visit program for Ph.D. candidates, as previously mentioned. According to the stipulations, candidates are expected to submit a journal paper before returning to their home country. Unfortunately, many awardees, including several in my batch, have struggled to fulfill this requirement. I can count on one hand the number of awardees in my batch who managed to submit a paper to a journal with their host professor during the research visit program. Given that the primary goal of this scholarship is to advance Indonesian research through international collaboration, the fact that approximately 90% of students are unable to deliver an international collaboration paper with their host university professor is concerning. This situation seems to undermine the intended impact of the scholarship and raises questions about the effective utilization of funds.

What makes the lack of quality

The lack of high-quality publications could be attributed to the recruitment process and gatekeeping culture among Indonesian officials. As previously stated, recruitment for this scholarship was not open to all Indonesians. I tried to promote this scholarship to my friends, who I believe are deserving of it, but they declined to apply since they were unaware of the perks and requirements. Most of them were also hesitant to apply since they believed they were not qualified enough. I think that the scholarship has a terrifying vibe (you have to be extremely active and intelligent to apply). However, as previously stated, I believed that the grantees who eventually received the scholarship were not as bright as my college classmates.

What should we do about it?

I acknowledge that expressing dissatisfaction alone won’t alter the existing situation. Nevertheless, the main motivation behind writing this post is to shed light on the operational nuances of my home country, which might appear strange and displeasing to some. Inclusion of more diverse individuals within a research team could prove beneficial in providing opportunities to people from varied backgrounds and countries. I understand that some professors overseas may have become skeptical of recruiting more Indonesians, given the mentioned mindset and behavior, leading to instances of non-delivery. Yet, I remain hopeful that global experts do not give up on minorities and continue extending opportunities.

Also, I hope such Indonesian scholarship programs will spread and reach a broader spectrum of motivated individuals who are unafraid to exhibit distinctive behavior and thinking. Despite the abundance of such scholarship initiatives, I am uncertain whether they are reaching the right and deserving recipients.

Perhaps I shouldn’t be overly critical about the lack of motivation among the majority of Indonesians. It is understandable, considering the numerous challenges posed by a society that is often radical or closed-minded, hindering the success of many Indonesian youth. This pattern has persisted across generations, including my own, my mother’s, and those preceding. That is why, I earnestly hope for a positive shift to commence with my generation, as Peter Carey anticipated. To achieve success in global research and education, more young individuals need to embrace open-mindedness, acceptance, and engagement with diverse cultures, languages, and perspectives.

I quote from Peter Carey’s Why has Indonesia never won a Nobel Prize?:

Be that as it may, whatever may happen in the Islamic world, Indonesia needs radical surgery, otherwise seven years hence, when it begins to experience an ageing population, it will be a stricken giant and hugely vulnerable. ‘‘We will seek knowledge all over the world and make it our own”—the Meiji shibboleth should be Indonesia’s rallying cry along with the reflections of the great Sufi poet-philosopher Rumi (1207-1273): “Go with all, take the name of all, speak the language of all, to everyone say yes, yes, yes! BUT DWELL IN YOUR OWN VILLAGE!”. In other words. become a global citizen without losing your own unique cultural identity. The examples of the Indian Nobel laureate in literature (1913), Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), and the Palestinian-born Edward Said (1935-2003), who brilliantly succeeded in becoming rooted cosmopolitan intellectuals, come to mind here. Producing Indonesian scholars, thinkers and public intellectuals of the calibre of Tagore and Said and ensuring that the physical achievement of independence is followed—as President Sukarno (in office, 1945-1966) constantly reminded us —by a decolonisation of the mind—that in my view, is the principal challenge of Indonesian universities today. In Sukarno’s words: “Never abandon the history of your past, O, my People, for if you abandon the history of your past, you will stand in a vacuum, you will stand upon emptiness, and then you will become confused, and your struggle will, at the most, be just mere running amuck! Running amuck like monkeys caught in the dark!”